Edmund Spenser

Birth and early years

Edmund Spenser was born in London near the Tower in the year 1552. His parents were poor, though they were probably connected with the Lancashire branch of the old family of Le Despensers, “a house of ancient fame,” from which the Northampton Spencers were also descended. The poet’s familiarity with the rural life and dialect of the north country supports the theory that as a boy he spent some time in Lancashire. Beyond two or three facts, nothing is known with certainty about his early years. He himself tells us that his mother’s name was Elizabeth and that London was his “most kindly nurse.” His name is mentioned as one of six poor pupils of the Merchant Taylors’ School, who received assistance from a generous country squire.

Youth and education

At the age of seventeen, Master Edmund became a student in Pembroke Hall, one of the colleges of the great University of Cambridge. His position was that of a sizar, or paid scholar, who was exempt from the payment of tuition fees and earned his way by serving in the dining hall or performing other menial duties. His poverty, however, did not prevent him from forming many helpful friendships with his fellow students. Among his most valued friends he numbered Launcelot Andrews, afterward Bishop of Winchester, Edward Kirke, a young man of Spenser’s own age, who soon after edited his friend’s first important poem, the Shepheards Calender, with elaborate notes, and most important of all, the famous classical scholar, a fellow of Pembroke, Gabriel Harvey, who was a few years older than Spenser, and was later immortalized as the Hobbinoll of the Faerie Queene. It was by Harvey that the poet was introduced to Sir Philip Sidney, the most accomplished gentleman in England, and a favorite of Queen Elizabeth.

Spenser’s residence in Cambridge extended over seven years, during which he received the usual degrees of bachelor and master of arts. He became one of the most learned of English poets, and we may infer that while at this seat of learning he laid the foundations for his wide scholarship in the diligent study of the Greek and Latin classics, the philosophy of Plato and Aristotle, the pastoral poetry of Theocritus and Vergil, and the great mediæval epics of Italian literature. On account of some misunderstanding with the master and tutors of his college, Spenser failed to receive the appointment to a fellowship, and left the University in 1576, at the age of twenty-four. His failure to attain the highest scholastic recognition was due, it is supposed, to his being involved in some of the dangerous controversies which were ripe in Cambridge at that time “with daily spawning of new opinions and heresies in divinity, in philosophy, in humanity, and in manners.”

Early Life and Marriage

As with so many people of his day, Spenser's early life is something of a mystery. Few records were kept of his younger years and even his year of birth is not certain. He was most likely born in 1552 or 1553 in London, England, where he spent much of his life. Unlike some other writers of the time, Spenser did not come from wealth. He studied at the merchant Taylor's grammar school where he received an education in the classics. Between 1569 and 1576, Spenser studied at Cambridge University. He also did some menial work for his college since he did not have the funds to pay his way through an undergraduate and a master's degree in the arts.

After graduating, Spenser worked for the Earl of Leicester, performing some diplomatic missions abroad on his behalf. He then returned to London and met fellow poet Sir Philip Sidney. In 1579, Spenser married a woman named Machabyas Chylde. The marriage lasted until her death, which was probably in 1593 or 1594. After his first wife's death, Spenser married a woman named Elizabeth Boyle in 1594 and remained married to her until his own death in 1599.

Early works

The Shepheardes Calender can be called the first work of the English literary Renaissance. Following the example of Virgil and of many later poets, Spenser was beginning his career with a series of eclogues has been of some interest in literary criticism.The Calender consists of 12 eclogues, one named after each month of the year. One of the shepherds, Colin Clout, who excels in poetry but is ruined by his hopeless love for one Rosalind, is Spenser himself. The eclogue “Aprill” is in praise of the shepherdess Elisa, really the queen (Elizabeth I) herself. “October” examines the various kinds of verse composition and suggests how discouraging it is for a modern poet to try for success in any of them. Most of the eclogues, however, concern good or bad shepherds—that is to say, pastors—of Christian congregations. The Calender was well received in its day, and it is still a revelation of what could be done poetically in English after a long period of much mediocrity and provinciality. The archaic quality of its language, sometimes deplored, was partly motivated by a desire to continue older English poetic traditions, such as that of Geoffrey Chaucer. Archaic vocabulary is not so marked a feature of Spenser’s later work.

The years 1578–80 probably produced more changes in Spenser’s life than any other corresponding period. He appears by 1580 to have been serving the fascinating, highly placed, and unscrupulous Robert Dudley, earl of Leicester and to have become a member of the literary circle led by Sir Philip Sidney, Leicester’s nephew, to whom the Calender was dedicated and who praised it in his important critical work The Defence of Poesie (1595). Spenser remained permanently devoted to this brilliant writer and good nobleman, embodied him variously in his own poetry, and mourned his early death in an elegy. By 1580 Spenser had also started work on The Faerie Queene, and in the previous year, he had apparently married one Machabyas Chylde. Interesting sidelights on his personal character, of which next to nothing is known, are given in a small collection of letters between Spenser and Gabriel Harvey that was printed in 1580. The ironies in that exchange of letters are so intricate, however, as to make it difficult to draw many conclusions from them about Spenser, except that he was young, ambitious, accomplished, and sincerely interested in the theory and practice of poetry. In 1580 Spenser was made secretary to the new lord deputy of Ireland, Arthur Lord Grey, who was a friend of the Sidney family.

Edmund Spenser’s Famous works

- The Faerie Queene-1590

- Amoretti-1595

- Epithalamion-1995

- Prothalamion-1996

- The Shepheardes Calender-1579

- The Mutabilitie cantos-1590

- Colin Clouts Come Home Againe-1595

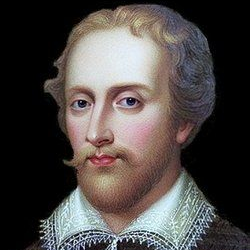

Spenser’s appearance

In personal appearance, Spenser was a fine type of sixteenth-century gentleman. The grace and dignity of his bearing was enhanced by a face of tender and thoughtful expression in which warmth of feeling was subdued by the informing spirit of refinement, truthfulness, simplicity, and nobility. He possessed a fine dome-like forehead, curling hair, brown eyes, full sensuous lips, and a nose that was straight and strongly molded. His long spare face was adorned with a full mustache and a closely cropped Van Dyke beard.

Career in Ireland

In 1580 Spenser went over to Ireland as private secretary to Lord Grey of Wilton, the Artegall of the Legend of Justice in the Faerie Queene. After the recall of his patron he remained in that turbulent island in various civil positions for the rest of his life, with the exception of two or three visits and a last sad flight to England. For seven years he was clerk of the Court of Chancery in Dublin, and then was appointed clerk to the Council of Munster. In 1586 he was granted the forfeited estate of the Earl of Desmond in Cork County, and two years later took up his residence in Kilcolman Castle, which was beautifully situated on a lake with a distant view of mountains. In the disturbed political condition of the country, life here seemed a sort of exile to the poet, but its very loneliness and danger gave the stimulus needed for the development of his peculiar genius.

“Here,” says Mr. Stopford Brooke, “at the foot of the Galtees, and bordered to the north by the wild country, the scenery of which is frequently painted in the Faerie Queene and in whose woods and savage places such adventures constantly took place in the service of Elizabeth as are recorded in the Faerie Queene, the first three books of that great poem were finished.” Spenser had spent the first three years of his residence at Kilcolman at work on this masterpiece, which had begun in England, under the encouragement of Sidney, probably before 1580. The knightly Sidney died heroically at the battle of Zutphen, in 1586, and Spenser voiced the lament of all England in the beautiful pastoral elegy Astrophel which he composed in memory of “the noblest and valorous knight.”

In Mother Hubbards Tale he makes a direct reference to the problematic nature of prepends:

“How manie honest men see ye arize

Daylie thereby, and grow to goodly prize;

To Deanes, to Archdeacons; to Commissaries,

To Lords, to Principalls, to Prependaries?”

Soon after coming to Ireland, Spenser made the acquaintance of Sir Walter Raleigh, which erelong ripened into an intimate friendship. A memorable visit from Raleigh, who was now a neighbor of the poet’s, having also received a part of the forfeited Desmond estate, led to the publication of the Faerie Queene. Sitting under the shade “of the green alders of the Mulla’s shore,” Spenser read to his guest the first books of his poem. So pleased was Raleigh that he persuaded the poet to accompany him to London, and there lay his poem at the feet of the great queen, whose praises he had so gloriously sung. The trip was made, Spenser was presented to Elizabeth, and read to her Majesty the three Legends of Holiness, Temperance, and Chastity. She was delighted with the fragmentary epic in which she heard herself delicately complimented in turn as Gloriana, Belphoebe, and Britomart, conferred upon the poet a pension of £50 yearly and permitted the Faerie Queene to be published with a dedication to herself. Launched under such auspices, it is no wonder that the poem was received by the court and all of England with unprecedented applause.

The last lines of The Faerie Queene have also been taken to refer back to this incident; Spenser hopes that his work will be read fairly, unlike his 'former writs', and so be:

“Free from all that white [blame],

With which some wicked tongues did it backbite,

And bring into a mighty Peres displeasure.”

The next year while still in London, Spenser collected his early poems and issued them under the title of Complaints. In this volume were the Ruins of Time and the Tears of the Muses, two poems on the indifference shown to literature before 1580, and the remarkable Mother Hubbards Tale, a bitter satire on the army, the court, the church, and politics. His Daphnaida was also published about the same time. On his return to Ireland, he gave a charming picture of life at Kilcolman Castle, with an account of his visit to the court, in Colin Clout’s Come Home Again. The story of the long and desperate courtship of his second love, Elizabeth, whom he wedded in 1594, is told in the Amoretti, a sonnet sequence full of passion and tenderness. His rapturous wedding ode, the Epithalamion, which is, by general consent, the most glorious bridal song in our language, and the most perfect of all his poems in its freshness, purity, and passion, was also published in 1595. The next year Spenser was back in London and published the Prothalamion, a lovely ode on the marriage of Lord Worcester’s daughters, and his four Hymns on Love and Beauty, Heavenly Love, and Heavenly Beauty. The first two Hymns are early poems, and the two latter are maturer works embodying Petrarch’s philosophy, which teaches that earthly love is a ladder that leads men to the love of God. In this year, 1596, also appeared the last three books of the Faerie Queene, containing the Legends of Friendship, Justice, and Courtesy.

Spenser: Poet and Writer

Although Edmund Spenser, poet and scholar, began writing verse during or shortly after his Cambridge years, he did not publish his first volume of work until 1579 or 1580. It was a series of twelve poems collectively titled The Shepherd's Calendar (or The Shepheardes Calender) through which Spenser explored pastoralism and satire. He was inspired in part by writers like Virgil whose work he greatly admired. The Shepherd's Calendar, as well as many of his later works, dealt with satirical social commentary and his concern for the stability and maintenance of the Church of England following the relatively recent English Protestant reformation.

Spenser was famous for his technical grasp of English in his poetry as well as his use of satire and his flattery of the monarchy and the court in many of his works. He was recognized as a great poet within his own lifetime, though he carried out a simultaneous diplomatic and political career for several decades. In 1580, Spenser became the secretary of Arthur Lord Grey, lord deputy of Ireland, and he spent the next several years living and working in Ireland with his family. He was respected in politics and his works also did well, allowing him to reach a broader audience because of his public-facing role.

Literary success; political and legal difficulties

At the height of his fame, happiness, and prosperity, Spenser returned for the last time to Ireland in 1597, and was recommended by the queen for the office of Sheriff of Cork. Surrounded by his beloved wife and children, his domestic life was serene and happy, but in gloomy contrast his public life was stormy and full of anxiety and danger. He was the acknowledged prince of living poets, and was planning the completion of his mighty epic of the private virtues in twelve books, to be followed by twelve more on the civic virtues. The native Irish had steadily withstood his claim to the estate, and continually harassed him with lawsuits. They detested their foreign oppressors and awaited a favorable opportunity to rise. Discord and riot increased on all sides. The ever growing murmurs of discontent gave place to cries for vengeance and unrepressed acts of hostility. Finally, in the fall of 1598, there occurred a fearful uprising known as Tyrone’s Rebellion, in which the outraged peasants fiercely attacked the castle, plundering and burning. Spenser and his family barely escaped with their lives. According to one old tradition, an infant child was left behind in the hurried flight and perished in the flames; but this has been shown to be but one of the wild rumors repeated to exaggerate the horror of the uprising. Long after Spenser’s death, it was also rumored that the last six books of the Faerie Queene had been lost in the flight; but the story is now utterly discredited.

Later Life and Death

Around 1590, having written a significant portion of his major oeuvre, The Faerie Queene, Spenser returned to England. He published the first several books of the poem as well as several of his other works. The Faerie Queene gained Spenser favor with Queen Elizabeth I; she gave him a modest lifelong pension as thanks.

Spenser once more arrived in London, but he was now in dire distress and prostrated by the hardships which he had suffered. There on January 16, 1599, at a tavern in King Street, Westminster, the great poet died brokenhearted and in poverty. Drummond of Hawthornden states that Ben Jonson told him that Spenser “died for lack of bread in King Street, and refused 20 pieces sent to him by my Lord of Essex, and said He was sorrie he had no time to spend them.” The story is probably a bit of exaggerated gossip. He was buried close to the tomb of Chaucer in the Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey, his fellow-poets bearing the pall, and the Earl of Essex defraying the expenses of the funeral. Referring to the death of Spenser’s great contemporary, Basse wrote:—

“Renownèd Spenser, lie a thought more nigh

To learnèd Chaucer, and rare Beaumont, lie

A little nearer Spenser, to make room

For Shakespeare in your threefold, fourfold tomb.”

“Thus,” says Mr. Stopford Brooke, appropriately, “London, ‘his most kindly nurse,’ takes care also of his dust, and England keeps him in her love.”

Work Cited

- Albert, Edward. History of English Literature. 2017. Accessed 5 November 2022.

- Blakeley, Sasha. “Edmund Spenser Poems & Biography | Who Was Edmund Spenser? - Video & Lesson Transcript.” Study.com, 14 March 2022, https://study.com/learn/lesson/edmund-spenser-poems-biography.html. Accessed 5 November 2022.

- Hadfield, Andrew. “Spenser, Edmund (1552?–1599), poet and administrator in Ireland.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 13 May 2021, https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-26145. Accessed 5 November 2022.

- Hieatt, Kent. “Edmund Spenser | English poet | Britannica.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 9 Jan 2022, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Edmund-Spenser. Accessed 5 November 2022.

- Thomson, James, et al. “Edmund Spenser Biography.” Excellence in Literature, 24 October 2014, https://www.excellence-in-literature.com/edmund-spenser-biography/. Accessed 5 November 2022.

Word Count 2934